General Shalikashvili achieved the highest ranking position in the US military. He joined the United State Army as a private, served in every level of unit command from platoon to division, and rose to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. As a Georgian he was also the first foreign-born Joint Chiefs Chairman. He was also the first draftee and first graduate of Officer Candidate School to hold the position.

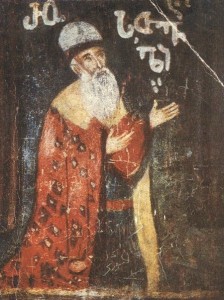

John Malchase David Shalikashvili was born in Warsaw, Poland, a descendant of the Georgian noble house of Shalikashvili. His father, Prince Dimitri Shalikashvili served in the army of Imperial Russia, and was a grandson of Russian general Dmitry Staroselsky. The princely “Schalikashvili” family of Georgia traces its lineage back at least to the year 1400.

In 1952, when Shalikashvili was 16, the family immigrated to Peoria, Illinois. He spoke little English when he arrived in Peoria but learned the language by watching American movies. He attended Bradley University in Peoria and earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1958.

After graduation he received a draft notice and entered the Army as a private. He later applied to Officer Candidate School and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1959. Shalikashvili served in various Field Artillery and Air Defense Artillery positions as a platoon leader, forward observer, instructor, and student, in various staff positions, and as a battery commander. He served in Vietnam as a senior district advisor from 1968 to 1969, and was awarded a Bronze Star with “V” for heroism during his Vietnam tour. In 1970, he became executive officer of the 2nd Battalion, 18th Field Artillery at Fort Lewis, Washington. Later in 1975, he commanded 1st Battalion, 84th Field Artillery, 9th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis. In 1977, he attended the U.S. Army War College and served as the Commander of Division Artillery for the 1st Armored Division in Germany. He later became the assistant division commander. In 1987, Shalikashvili commanded the 9th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis, where he oversaw a “high technology test bed” tasked to integrate three brigades—one heavy armor, one light infantry, and one “experimental mechanized”—into a new type of fighting force.

One of his most notable achievements was directing the relief program, Operation Provide Comfort. In April 1991 Lieutenant General Shalikashvili went to northern Iraq to avert a humanitarian crisis following the end of the first Gulf War. The Iraq army forced over 500,000 Kurds into the inhospitable mountains along the Turkish border. Lacking food, water, and shelter, approximately 1000 Kurdish men, women, and children were dying each day. Shalikashvili led a massive relief mission to rescue the Kurds. The operation eventually involved 35,000 soldiers from 13 countries as well as volunteers from over 50 Non-Government Organizations working together effectively. The operation first delivered life-saving supplies and then turned the effort to establishing safe refuge. His troops worked with relief agencies to build the camps while also confronting threats from hostile Iraqi army forces. Shalikashvili met with Iraqi forces, warning them of the risks of attacking the relief effort. Hostilities were avoided, leaving the coalition troops to focus on assisting the displaced. Shalikashvili’s command saved lives, brought order, and allowed the more than 500,000 displaced to return to their homes within several months. General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs at the time, would later say that General Shalikashvili had worked “a miracle.”

In August 1991 General Powell recognizing Shalikashvili’s leadership skills and organizational ability, called him back to Washington, D.C., as his assistant. Shalikashvili had demonstrated great diplomacy and logistics skills and Powell noted that he was able to operate in new conceptual territory with ease. In 1992 Shalikashvili was named Supreme Allied Commander Europe, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). His knowledge of Europe and ability to speak Polish, Russian, and German played a role in this assignment.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton appointed Shalikashvili as the 13th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. President Clinton referred to him as “General Shali,” a soldier’s soldier. The president, in calling him General Shali, followed the affectionate name used by the general’s staff. As chairman, Shalikashvili advised President Clinton on military and humanitarian missions to Haiti, Rwanda, Bosnia, and the Persian Gulf. He oversaw more than 40 operations and sought greater integration of military and civilian agencies operating jointly to respond to humanitarian crises. He also continued the efforts of his predecessor Colin Powell at improving joint operations with the various military branches. Shalikashvili had the difficult task of reducing the military budget to realize a “peace dividend.” This included cutting unneeded weapons systems and the 1995 Base Realignment and Closure Act. He completed his chairman’s tour in 1997 and retired. At his retirement ceremony President Clinton awarded him the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award recognizing the General for working “tirelessly to improve our Nation’s security and promote world peace.

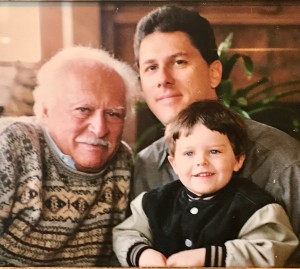

General Shalikashvili visited Georgia together with his brother, a retired colonel from the US Special Forces Othar Shalikashvili, in May, 1995. While in Georgia, they travelled to Kakheti region, to the home region of their ancestors – Gurjaani. They also met with the then head of Georgian state, Eduard Shevardnadze.

Following retirement, Shalikashvili was an advisor to John Kerry’s 2004 Presidential campaign. He was a visiting professor at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University, and served in various capacities with a number of businesses. In 2006 the National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) launched the John M. Shalikashvili Chair in National Security Studies to recognize Shalikashvili for his years of military service and for his leadership on NBR’s Board of Directors.

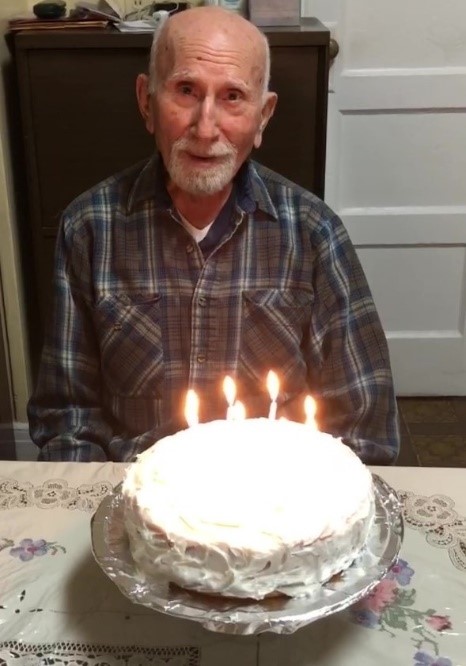

Shalikashvili died at the age of 75 on July 23, 2011, at the Madigan Army Medical Center in Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Upon his passing, President Barack Obama said that the United States lost a “genuine soldier-statesman,” adding in a statement that Shalikashvili’s “extraordinary life represented the promise of America and the limitless possibilities that are open to those who choose to serve it.”

Former president Clinton pointed out that “Gen. Shali” made the recommendations that sent U.S. troops to Haiti, Rwanda, Bosnia, the Persian Gulf and a host of other world hotspots that had proliferated since the end of the Cold War. “He never minced words, he never postured or pulled punches, he never shied away from tough issues or tough calls, and most important, he never shied away from doing what he believed was the right thing,” Clinton said.

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said in a statement that he relied on Shalikashvili’s advice and candor when he served as Clinton’s chief of staff during the foreign policy crises in Haiti, the Balkans and elsewhere. “John was an extraordinary patriot who faithfully defended this country for four decades, rising to the very pinnacle of the military profession,” Panetta said. “I will remember John as always being a stalwart advocate for the brave men and women who don the uniform and stand guard over this nation.”

The then chairman, Adm. Mike Mullen, said Shalikashvili “skillfully shepherded our military through the early years of the post-Cold War era, helping to redefine both U.S. and NATO relationships with former members of the Warsaw Pact.”

John Shalikashvili left a proud legacy for all Georgians.

portrayal of the Madonna in Max Reinhardt’s unique 1911 pantomime spectacle play The Miracle. He briefly served as the Georgian ambassador to Italy until the establishment of Soviet rule in Georgia in 1921. He and his wife then moved to the United States. Mr. Matchabeli wanted American citizenship, but wasn’t willing to relinquish the glamour of his title as Prince, so he petitioned for the right to use the title as his first name. So from 1934 onward, he was Mr. Prince Matchabeli. The prince was an amateur chemist who began creating perfumes for his friends and family as a hobby. In 1924 he and his wife, now known as Princess Norina Matchabeli, established the Prince Matchabeli Perfume Company. Norina designed the crown shaped perfume vial in the likeness of the Matchabeli crown. His first employees were all fellow exiled aristocrats. One Georgian writer of the time remembered them as the most courteous staff in the United States and the prince himself was a perfect spokesman for his product. He had a reputation for exquisite manners and refined appearance, ideal for selling perfume to American women. In 1928, Matchabeli’s perfumes were awarded the Grand Prix with gold medal at the expositions in Paris and Liege for their quality and originality.

portrayal of the Madonna in Max Reinhardt’s unique 1911 pantomime spectacle play The Miracle. He briefly served as the Georgian ambassador to Italy until the establishment of Soviet rule in Georgia in 1921. He and his wife then moved to the United States. Mr. Matchabeli wanted American citizenship, but wasn’t willing to relinquish the glamour of his title as Prince, so he petitioned for the right to use the title as his first name. So from 1934 onward, he was Mr. Prince Matchabeli. The prince was an amateur chemist who began creating perfumes for his friends and family as a hobby. In 1924 he and his wife, now known as Princess Norina Matchabeli, established the Prince Matchabeli Perfume Company. Norina designed the crown shaped perfume vial in the likeness of the Matchabeli crown. His first employees were all fellow exiled aristocrats. One Georgian writer of the time remembered them as the most courteous staff in the United States and the prince himself was a perfect spokesman for his product. He had a reputation for exquisite manners and refined appearance, ideal for selling perfume to American women. In 1928, Matchabeli’s perfumes were awarded the Grand Prix with gold medal at the expositions in Paris and Liege for their quality and originality. legend says that the poet abandoned public life, became a monk, and spent the rest of his days in one of the Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem (formerly the Georgian Monastery of the Holy Cross, the church now belongs to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem). It was there that his tomb was discovered centuries later, along with a fresco and a simple inscription “Shotha Rustaveli”. His Wikipedia Biography notes that the fresco and accompanying inscription in Georgian were defaced in 2004. But the fresco was subsequently restored.

legend says that the poet abandoned public life, became a monk, and spent the rest of his days in one of the Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem (formerly the Georgian Monastery of the Holy Cross, the church now belongs to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem). It was there that his tomb was discovered centuries later, along with a fresco and a simple inscription “Shotha Rustaveli”. His Wikipedia Biography notes that the fresco and accompanying inscription in Georgian were defaced in 2004. But the fresco was subsequently restored.